Congratulations to Professor Christopher Hanscom on the publication of his newest book, The Affect of Difference: Representations of Race in East Asian Empire. Takashi Fujitani, author of Race for Empire has this to say, “This stunning collection is a major intervention in the study of empire and its afterlives that richly details the historical and regional singularities of the Japanese imperial formation even as it provocatively opens up questions of imperialism and racism as aspects of global modernity. Exceedingly well written and sophisticated without pretense, this book will appeal to anyone with an interest in imperialism, whether inside or outside of the East Asian context.”

Click here to learn more about Professor Hanscom’s book.

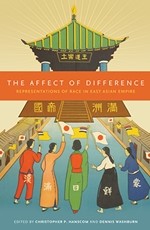

The Affect of Difference: Representations of Race in East Asian Empire

Edited by Christopher P. Hanscom and Dennis Washburn

Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2016

The Affect of Difference is a collection of essays offering a new perspective on the history of race and racial ideologies in modern East Asia. Contributors approach this subject through the exploration of everyday culture from a range of academic disciplines, each working to show how race was made visible and present as a potential means of identification. By analyzing artifacts from diverse media including travelogues, records of speech, photographs, radio broadcasts, surgical techniques, tattoos, anthropometric postcards, fiction, the popular press, film and soundtracks—an archive that chronicles the quotidian experiences of the colonized—their essays shed light on the politics of inclusion and exclusion that underpinned Japanese empire.

One way this volume sets itself apart is in its use of affect as a key analytical category. Colonial politics depended heavily on the sentiments and moods aroused by media representations of race, and authorities promoted strategies that included the colonized as imperial subjects while simultaneously excluding them on the basis of “natural” differences. Chapters demonstrate how this dynamic operated by showing the close attention of empire to intimate matters including language, dress, sexuality, family, and hygiene.

The focus on affect elucidates the representational logic of both imperialist and racist discourses by providing a way to talk about inequalities that are not clear cut, to show gradations of power or shifts in definitions of normality that are otherwise difficult to discern, and to present a finely grained perspective on everyday life under racist empire. It also alerts us to the subtle, often unseen ways in which imperial or racist affects may operate beyond the reach of our methodologies.

Taken together, the essays in this volume bring the case of Japanese empire into comparative proximity with other imperial situations and contribute to a deeper, more sophisticated understanding of the role that race has played in East Asian empire.